Difference between revisions of "(Historic) Roderick Sprague"

(Created page with "thumb|Roderick Sprague thumb|Roderick Sprague thumb|Roderick Sprague File:Scie...") |

m (Darkwing moved page (Historical) Roderick Sprague to (Historic) Roderick Sprague without leaving a redirect) |

(No difference)

| |

Latest revision as of 13:35, 31 May 2024

From Loren Coleman

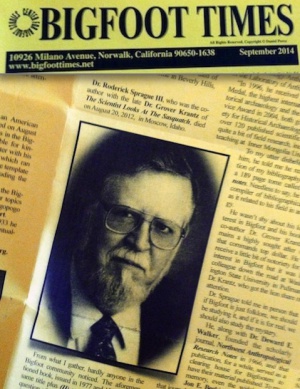

Daniel Perez’s September 2014 Bigfoot Times brings to my attention the sad news that traditional archaeologist and teaching anthropologist Roderick (“Rick”) Sprague passed away on August 20, 2012.

“From what I gather,” writes Perez, “hardly anyone in the Bigfoot community noticed.”

I would have to concede that Perez’s observation is on target.

Unfortunately, late in August 2012, news of death in the Bigfoot field was focussed on Randy Lee Tenley, 44, of Kalispell, Montana, who was killed a few days after Sprague died. Tenley, as you may recall, was hit by two cars, as he was wearing a Ghillie suit, dressed as a Bigfoot, and trying to create a Sasquatch (hoax) sighting on U.S. Highway 93.

Don’t read me wrong. The discussions and news about Tenley’s death are no excuse, and I feel badly for not having been aware of Sprague’s passing before now. Sprague was a good man, excellent scientist, and we all should have recalled him back then for the greatness he shared with many of us.

Sprague’s work in anthropology was admired and well-known. “Roderick Sprague III (February 18, 1933 – August 20, 2012) was a renowned American anthropologist, ethnohistorian and historical archaeologist, and the Emeritus Director of the Laboratory of Anthropology at the University of Idaho in Moscow, where he taught for thirty years. He had extensive experience in environmental impact research, trade beads, aboriginal burial customs, and the Columbia Basin area,” would note an anonymous writer at Wikipedia. “In addition to his work in the traditional anthropological fields, he also collaborated with Professor Grover Krantz in an attempt to apply scientific reasoning to the study of Sasquatch.”

It appears Sprague was not unfamiliar with finding the rare discovery: As a graduate student in 1964 at Washington State University, he was the field supervisor of a dig at the Palus burial site in Lyons Ferry, Washington State, when one of only a few known Jefferson Peace Medals was discovered. His doctoral dissertation was on burial technology, and his book on that topic is today considered a reference work of some note.

Sprague, along with Dr. Deward E. Walker, founded the scholarly journal Northwest Anthropological Research Notes in 1966, called the Journal of Northwest Anthropology since 2001.

It was through the journal he founded and his scientific point-of-view that Sprague would publish his most detailed work on Sasquatch.

- The Scientist Looks at the Sasquatch (Moscow: University Press of Idaho, 1977, with Grover Krantz)

- The Scientist Looks at the Sasquatch II (Moscow: University Press of Idaho, 1979, also with Grover Krantz, ISBN 0-89301-061-8)

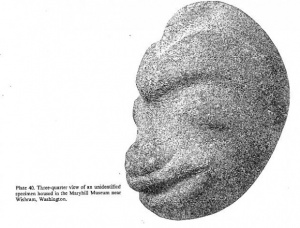

Roderick Sprague’s work in Sasquatch artifacts included the paper, “Carved Stone Heads of the Columbia River,” which is to be found in Marjorie M. Halpin & Michael M. Ames (Eds.), Manlike Monsters on Trial; Early Records and Modern Evidence, (Univ. of BC Press, Vancouver, 1980) pp. 228-234.

Sprague was open to others’ points of views on his writings, however. As Sprague noted about the above-mentioned paper, “The only reaction (negative) was from my long-time friend, B. Robert Butler, who had loaned me prints for one of the illustrations, and his reaction was prior to publication. I would have to agree with Butler that some of the ‘ape heads’ represent female mountain sheep in estrus – when their lips are pulled back exposing the teeth.” Source.

Sprague was a critique of all in the field, and was as insightful about his friends, as he was on the debunkers. On Grover Krantz, Sprague once observed:

Grover Krantz, in “Sasquatch Believers vs. the Skeptics,” fully intended to insult both the “scientific” skeptic and the true believer. If the scientific community were to read his chapter, they would be insulted, but, unfortunately, they already have all the facts and will not read it. On the other hand, the true believers will read it, be insulted, and go on their merry way ignoring Krantz’s message.

It is Krantz’s willingness to openly investigate the unknown that has cost him the respect of many colleagues as well as timely academic promotion. Likewise, his unwillingness to be a fanatical believer in a religious sense has alienated him from most of the non-academic investigators. Like the Man Without a Country, he is cast afloat, awaiting the day of discovery-when he will “enjoy seeing a lot of people eat crow.” It is no accident that Krantz and I edited a book together. Not because we are good friends or close colleagues, which we are not, nor because we both originally believed in the existence of Sasquatch, which I did not, but because we both believed, as scientists, that the phenomenon known as Sasquatch should be studied, and such studies should be published. To call the study of Sasquatch “like the study of little green men from Mars,” as one of Krantz’s former university administrators once said, could be called as anti-intellectual as the Spanish Inquisition.

For example, also, in the International Society of Cryptozoology’s journal Cryptozoology, Volume 5 (1986), Roderick Sprague had some positive and negative things to say about my research on Amerindian folklore and on the southern USA reports of anthropoids/pongoids in his review of Vladimir Markotic’s and Grover Krantz’s The Sasquatch and Other Unknown Hominoids (1978).

Loren Coleman and Mark Hall in “From ‘Atsen’ to Giants in North America,” continue in a highly readable but somewhat disorganized way the position taken by John Green several years ago that the stories by American Indians of large, smelly, hairy creatures are part of the American Indian natural world, and not part of their mythology as categorized by anthropologists. They admit that their “survey is not exhaustive” (p. 31), which it is not; but why not? Is this volume for popular consumption, or is it to report scientific research?

and

The last of the regional reports, Loren Coleman’s “The Occurrence of Wild Apes in North America,” makes two major contributions. First, his References Cited section is virtually all new material to the western North American Sasquatch researcher. Secondly, he has collected all of the southeastern United States data and proposed an hypothesis for why the footprints look different, and why the reported heights of such creatures are less than those reported for the Sasquatch. The introduction of Dryopithecus into the New World without any fossil continuum is a weak point in an otherwise well developed argument.

Now we know why Roderick Sprague’s voice has been silent. He has joined Grover Krantz and Wayne Suttles in death.

So where are Sprague’s files, a frequent question about researchers who have died? Sprague planned ahead.

On September 10, 2004, Joe Beelart wrote:

Yesterday, I had the privilege of speaking on the telephone with Mr. Roderick Sprague. Mr. Sprague is retired from the University of Idaho.

Mr. Sprague co-edited with Grover Krantz “The Scientist Looks at the Sasquatch” and “The Scientist Looks at the Sasquatch II.”

He told me that he donated his Bigfoot papers to the University of Idaho Archives at Moscow, Idaho. They are in two boxes located in the University Library Special Collection Archives listed under “Sprague/Sasquatch.” The current special collections director is Terry Abraham.

Looking at the papers requires a personal visit to the library.

Joe Beelart West Linn, Oregon

The Moscow-Pullman Daily News, published the following obituary on August 22, 2012, about Sprague:

Dr. Roderick Sprague III was born in Albany, Ore., on Feb. 18, 1933. He lived most of his life in Idaho, Washington and Oregon. He received his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in anthropology from Washington State University, served two years in the U.S. Army, and received his doctorate in anthropology from the University of Arizona, Tucson. He worked at WSU as a research archaeologist for three years before going to the University of Idaho in 1967 as an assistant professor of anthropology. Within a year and a half of his arrival he became chairman of the Department of Sociology/Anthropology and director of the Laboratory of Anthropology. After 12 1/2 years the two positions were separated and he remained the Laboratory of Anthropology director, but continued to teach anthropology part-time including summer archaeological field schools. One notable year was a sabbatical in 1986-1987 teaching at Inner Mongolia University as the first participant in the University of Idaho exchange with the institution.

Field work was conducted in Idaho, Washington, Oregon, Alaska, Arizona and Prince Edward Island. In 1986, he received both the University of Idaho Library Faculty Award for Outstanding Service and the Sigma Xi Published Research Paper Faculty Award. In 1996, he received the J.C. Harrington Medal, the highest international award in historical archaeology and the Carol Ruppe Service Award in 2004, both given by The Society for Historical Archaeology. Currently he remains the only member to ever receive both of these awards and the only member to serve two terms as president of the society.

During his career he published more than 120 scientific papers and articles plus more than 100 unpublished reports to agencies specializing in historical archaeology, culture change theory and artifact analysis including such areas as glass trade beads and buttons. He conducted research and burial excavations at the request of 10 different American Indian tribal governments in the Plateau, Great Basin and Northwest Coast with repatriation a standard procedure many years prior to the enactment of the federal Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act. Editorial duties involved 40 years as senior co-editor for the Journal of Northwest Anthropology, 96 of the 98 issues of the University of Idaho Anthropological Reports, 20 years as review editor for Historical Archaeology and serving on numerous editorial advisory boards.

He completed legal work for five different Northwest Tribes and two tribes outside of the area which involved testimony in the 5th District Federal Court on five occasions, including one case before the Supreme Court, as well as testimony before various state and federal legislative bodies.

After retirement he continued to live in Moscow, Idaho, with his wife, Linda. He was designated professor emeritus of anthropology and director emeritus of the Laboratory of Anthropology at the University of Idaho. He continued to conduct research and serve as an expert witness for Northwest tribes after retirement.

Rick was preceded in death by his parents, Roderick Sprague II and Mary Willis Sprague. He is survived by his wife, Linda Ferguson Sprague; two sisters Anne Geaudreau and her husband, Wain, and Arda and Bob (deceased) Rutherford; four children and two grandchildren, Roderick Sprague IV of Moscow, Idaho, Katherine Sprague and her partner, Tabitha Simmons, of Moscow, Frederick Sprague his wife, Dawn, and their son, Jack, of Renton, Wash., and Alexander his wife, Rebecca, and their son, Phineas, of Boise, Idaho.

(BTW, Sprague’s wife Linda, also holds degrees in anthropology.)