(Historic) Dr. David C. Oren

From Loren Coleman

The great cryptozoologist and rainforest biologist Dr. David C. Oren died, in his beloved, adopted home of Brazil, September 7, 2023. He was 70 years old.

Dr. Oren experienced a full existence of fieldwork, notoriety, and controversy. His death brings an end to his scrupulous work in studying the strange creature called “Mapinguari”—research which at times brought ridicule upon David. His passing presents an opportunity to review the status of the Mapinguari, and the life of its most dedicated modern researcher.

The Mapinguari in the 1950s

The Mapinguari has been discussed within cryptozoological literature for quite some time. In the 1950s-1960s, Frank W. Lane (in Nature Parade), Bernard Heuvelmans (in On the Track of Unknown Animals), and Ivan T. Sanderson (in Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come to Life), all focused on the Mapinguari in South America.

Typically, the Mapinguari, as described in local traditions, is ethnoknown throughout southern Brazil as a red-haired, sloping, bipedal, long-armed cryptid – associated with unique “bottle” footprints. Cryptozoologists, including Bernard Heuvelmans, Ivan T. Sanderson, Mark A. Hall, Loren Coleman, and others have long considered the Mapinguari a creature worthy of attention, as detailed in the Coleman and Jerome Clark book, Cryptozoology A to Z, published in 1999.

Bernard Heuvelmans theorized that the Mapinguari might be a large primate, and reinforced that notion in the journal Cryptozoology, Vol. 5, 1986, pages 21-22.

Heuvelmans had extensively reviewed and wrote about the possible late survival of ground sloths in his On the Track of Unknown Animals (France 1955, England 1958; p. 283). In a wonderful concluding statement on the Giant Sloth, Heuvelmans observed, “Might they not still live in this ‘green hell’ and find it as a heaven of peace?”

Ivan T. Sanderson as well studied the Mapinguari in some of his work. In his bible of Hominology, Abominable Snowmen: Legend Come To Life / The Story of Sub-Humans on Five Continents from the Early Ice Age Until Today (USA 1961), Sanderson’s overview of South American cryptozoology led him to find the sightings of what he felt were anthropoid apes worthy to consider too. (I shall never forget my first reading, in 1961, of Sanderson’s compelling word imagery of the Mapinguari pulling the tongues out of cattle. There seemed little doubt in my mind that it would take a strong hominoid’s hand to do that.)

Following my personal introduction to Southern American cryptozoology in the 1950s, the writings of biologists Bernard Heuvelmans and Ivan T. Sanderson continued to influence thought and discourse regarding reports of the Mapinguari on that continent. Cryptozoology scholars shared and retold the accounts of the giant cattle-tongue pulling apes in Brazil; and the records of the survival of giant ground sloths in southern Amazonia.

Enter Oren

Dr. David Oren expanded the discussion begun by the Heuvelmans-Sanderson midcentury view of allegedly extinct ground sloths in South America. Through Oren’s research, publications, interviews, and documentaries, as well as through direct correspondence with me and others in the field, Oren established his name in association with both South American ground sloths and Mapinguari, and the argument for a connection between the two.

In the 1990s, through the publication of Dr. Oren’s fieldwork in Brazil, he revealed to several of us a different possibility for Mapinguari: he did not consider these animals as primates, but he strongly outlined the evidence regarding reports of giant ground sloths and how these reports might be related to Mapinguari sightings. He did this not as a cryptozoologist, but as a biologist. Oren shared a new insight to what was happening in Brazil and surrounding lands.

The Origins of Oren

David Conway Oren was born in Jackson, Michigan, on May 20, 1953. He graduated in Biology from Yale University in 1975 and received a PhD in Biology in 1981. His dissertation, Zoogeographic Analysis of the White Sand Campina Vegetation of Amazonia, under the direction of Robert Edward Cook, earned him his PhD from Harvard. His speciality was ornithology. Oren travelled to the Amazon in 1977, studying the biogeography of birds of the rainforests of the region.

Oren chose Brazil as his home in 1981, naturalizing himself as a Brazilian as soon as he could. For years, he worked for the Emilio Goeldi Museum in Belém, one of Brazil’s foremost Amazon research centers, before transferring elsewhere in the field of conservation, in his adopted country. For Oren’s contributions to Brazilian ornithology, Brazilian and North American researchers described, in 2013, a new species of bird (Myrmotherula oreni) in his honor (although it has been demoted to a subspecies status since then). This species was later classified as a junior synonym of Ihering’s antwren (Myrmotherula iheringi).

Oren First Hears of Mapinguari

In 1988, after he established a deep commitment to Brazil, and after reading Heuvelmans’ foundational writings on the subject of cryptozoology, Oren first heard stories of the creature to which he would dedicate years of research: the Mapinguari—although he initially dismissed the report as only another legend. However, after an associate told of an encounter of his own, Oren looked further into the stories, and found several firsthand reports of the animal from indigenous Indians, including seven people who claimed to have killed a Mapinguari.

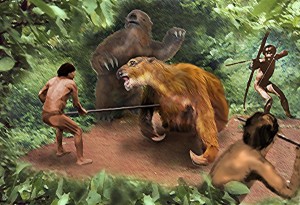

The rendering of a native Brazilian killing of a Mapinguari.

In a Goeldi Museum monograph in 1994, Oren hypothesized that Mapinguaris were real or, at least, recently extinct. He felt they may be the last extant giant ground sloths, and as such were Pleistocene survivors hidden in the tropics. Red-furred vegetarians with large claws that curled under and faced backward when they walked on all fours, they could stand on their hind feet like people, and some species had dermal ossicles, or bony plates that made their skin tough. They were thusly considered “bullet-proof” and “arrow-proof.” (In paleontological time frames, the giant ground sloths had recently disappeared, becoming extinct between 5,000 and 10,000 years ago.)

Mapinguari, Oren, and the Media

Thoughts of late-surviving giant and medium-sized ground sloths have a long history.

Vice President Thomas Jefferson asked explorers Lewis and Clark, as they planned their famous expedition in 1804–1806, to keep an eye out for living specimens of Megalonyx, as this would support Jefferson’s belief in their continued existence; his idea made no headway and was later shown to be incorrect. However, Jefferson’s notion that humans and Jefferson’s Giant Sloth Megalonyx co-existed in North America has been shown to be factual, as some bones of Megalonyx have marks on them made by flint tools.

The Caribbean ground sloths, the most recent survivors, lived in the Antilles, possibly until 1550 BCE. However, radiocarbon dating suggests an age of between 2819 and 2660 BCE for the last occurrence of Megalocnus in Cuba. They survived 5,000–6,000 years longer in the Caribbean than on the American mainland, which correlates with the later colonization of this area by humans. Could the ground sloths have existed longer in the “islands of the Amazon,” Oren wondered?

Giant sloths of many varieties lived, as part of the megafauna in South America, until at least 10,000 years ago. But cryptozoologists from Bernard Heuvelmans to David Oren speculated there was evidence for allegedly extinct ground sloth survival into modern times. There is reason to believe that the first South Americans hunted giant ground sloths, as “fresh” skin and dung were discovered in a cave in Argentina in 1895.

In the 1890s, the governor of Argentina, Ramon Lista, said he saw a creature, which might match the description of a medium-sized, hairy ground sloth, while he was hunting in Patagonia, giving further credibility to more recent reports of this prehistoric creature.

Though some declared Mapinguari sightings may indeed be of a fossil ground sloth, this conclusion was debatable in the early years of Oren’s studies. As Mark A. Hall wrote in the mid-1990s, “The popular discussions of David Oren’s research have done nothing to clear up the picture [regarding Mapinguari]. They may have only confused the issue all the more for the time being.”

David Oren Does His Fieldwork

After moving to Brazil, Oren began doing interviews with the Amazon’s indigenous people. Very soon in the the 1970s, he learned there was a Lazarus taxon that served as an example to which he pointed. Could the Mapinguari be an extinct animal yet to be verified? Had not the Chacoan peccary or tagua (Catagonus wagneri) just been discovered alive in 1972 (after first being described in 1930, based on fossils) in the Gran Chaco of Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina, south of Brazil? The native people were well aware of the tagua, but Western scientists were not willing to acknowledge its existence.

Oren wrote his first monograph on the Mapinguari-Giant Sloth theory in 1993. He had gathered first hand accounts.

“In the 1980s and 1990s, David Oren conducted 50 interviews with Brazilian Indians, rubber planters, and miners who know about the animal. One group of Kanamarí Indians living in the Rio Juruá valley claimed to have raised two infant Mapinguaris on bananas and milk; after one or two years their stench became unbearable and they were released,” George Eberhart wrote in his Mysterious Creatures (2002). “The ape-like variety is more often seen in Mato Grosso and Pará states, Brazil; and the sloth-like variety has been reported in Amazonas and Acre states, Brazil. Possible evidence also exists in Paraguay.”

David Oren has led a number of self-funded expeditions to the western Amazon in search of the Mapinguari, but alleged Mapinguari hair and stool acquired on these expeditions was identified as anteater hair and tapir feces. However, he has made casts of unidentified footprints similar to those of ground sloths, shown them on televised documentaries, and on a preliminary expedition in Spring 1993, he heard the roaring of an unknown animal four times on two separate occasions, in the afternoon and early night. He described the call as being extremely strong and of steady pitch, lasting for up to forty-five seconds, and resembling “jets flying over low.” He also possessed a photograph of “claw marks on a tree, eight of them about a foot long and an inch deep.”

Then in 2007, Oren received widespread media attention from NBC’s Today Show to the Sunday New York Times, a via news about a contemporary Mapinguari hunt, with the headline: ”Numerous Tribes See Brazillian ‘Bigfoot’.”

But the article wasn’t about “Bigfoot.” It contained comments on the locals having “spoken throughout the years of seeing a giant, fearsome, sloth-like creature that roams the rainforest.”

The July 8, 2007 / Sunday New York Times article about the Mapinguari caused the work of David Oren, his thoughts, and the Mapinguari, to become the center of a public discussion once again:

“It is quite clear to me that the legend of the Mapinguari is based on human contact with the last of the ground sloths,” thousands of years ago, said David Oren, a former director of research at the Goeldi Institute in Belém, at the mouth of the Amazon River. ”We know that extinct species can survive as legends for hundreds of years. But whether such an animal still exists or not is another question, one we can’t answer yet.”

David Oren’s initial gathering of Brazilian reports was followed by visits with villagers in which he interviewed several eyewitnesses using replica animals. Summaries of Oren’s work was overviewed by Karl Shaker, George Eberhart, Loren Coleman, and other cryptozoology chroniclers. By the time of the end of Oren’s field investigations, he had talked to 100 witnesses who described the Mapinguari first hand.

Oren, standing on the credibility of being a Harvard-educated biologist, redefined the issue in the 1990s, when he told the New York Times (and through Discovery magazine too) that Amazonians were in fact seeing supposedly extinct medium-sized ground sloths (apparently, the Mylodon, not the Megatherium).

What was unique about the David Oren documentary in the field was the footage of him interviewing the locals. He was shown using a Megatherium replica for these talks with the indigenous people, to gather more information about the sightings.

The special appeal of the Bullyland Megatherium, at 6.25″ tall, is its upright stance and a generally active appearance. The locals in Brazil responded positively to David Oren’s use of this replica during his Amazon rainforest interviews. The large size of the replica served as a good visual aide (despite the fact the German model maker Bullyland mistakenly had three-toes on each hind foot, instead of only one which is correct).

I was able to track down the model he was using, and soon after his mid-1990s’ expeditions, I obtained a copy for my collection. Oren and I exchanged emails, confirming his field replica, and he told me the frustrations were many for himself. (His steadfast research caused him troubles. Owing to Oren’s stance on the Maginguari, he was refused a position with the National Geographic Society, and received no funding. He used his own money for his expeditions.)

Oren was using a Bullyland Megatherium, as shown. The kind of replica that Oren employed reportedly has been discontinued, but it can sometimes be found at online auctions.

There are other Megatherium replicas available. Two others that are relatively easy to obtain are produced by Wild Safari and Schleich. I have examples of all three on display at the International Cryptozoology Museum.

Oren appeared in a number of cryptozoological TV shows, including Sightings (1995), Into the Unknown (1997), The Monster Files (1998), Destination Truth (2009), and Beast Hunter (2011).

Pat Spain hosted Nat Geo’s Beast Hunter/Travel Channel’s Legend Hunter (March 2011) and wrote a book Bulletproof Ground Sloth (2023) about his Mapinguari expedition and meeting with David Oren in Brazil. Spain was able to interview Oren regarding the giant ground sloth theory, and Oren gave Spain his version of the Mapinguari call, a slowed-down sloth scream. During Spain’s night investigation, the repeated call got a response.

Pat Spain, while open-mindedly skeptical, enjoyed his time with David Oren. When Spain was leaving Brazil, he recalled Oren’s last words. We should reflect on them here.

Pat Spain wrote in his book, “As I turned to walk away, like a scene out of a movie, David said: ‘I really do believe it’s there, you know.’” Pat nodded and said, ‘Yeah, I can see that.’ David went on: ‘You don’t – think it’s there I mean. That’s okay, don’t worry about it….It’s not a bad thing. But watch out – once you do believe, it’s really hard to to walk away from.’ Dr. David Oren gave a hangdog smile.

And now Oren has walked off into the rainforest of cryptozoological history.

Some final shared thoughts from Brazil… The Emilio Goeldi Museum wrote the following tribute (translated from the original Portuguese) upon David Oren’s death:

“David was an extremely cultured, polyglot person, who was in a permanent state of learning. An insightful observer had a unique memory, capable of remembering minimal details of the various cultures with which he had lived. Perfectionist, he was able to spend hours practicing until he learned to correctly pronounce words like mormaço, one of his favorites. David was an excellent teacher and mentor for several generations of Brazilian zoologists, guiding several dissertations and master’s degrees, participating in numerous evaluation boards and supporting the career development of several young researchers.…

“David was a passionate person. His relationship with the love of his life, Roberto, who left very early, inspired everyone around him. In the same way as his immense passion for Brazil was contagious. At his naturalization ceremony, for example, David was very sad and frustrated because he did not have the opportunity to sing the Brazilian national anthem and thus demonstrate his immense love for his new homeland.

“David was an extremely generous person. It helped everyone without distinction, even those who tried to harm him behind the scenes of life. Because of his generosity, David was loved and had many friends in various parts of the world. It is this network of friends that, despite crying, their unexpected departure comes together to celebrate and maintain their legacy forever.”

We shall miss him.