Missing link

The question or suggestion that sasquatches might be a (or the) "missing link" (between humans and other apes) is based on a false metaphor: there is actually no such thing as a 'missing link' as it is commonly used in the context of evolution.

Excerpt (and references) from 'Getting the Monkey off Darwin's Back: Four Common Myths About Evolution, Skeptical Inquirer, May 2005

The Missing Link

"Fossils May be Humans' Missing Link" reported the Washington Post on April 22, 1999. The story states that fossils discovered in Ethiopia ". . . may well be the long-sought immediate predecessor of human beings." But almost fifty years earlier, paleontologist Robert Broom published Finding the Missing Link (1950), about his discovery of fossil "ape men" in South African caves. And since 1950, reports of the discovery of "missing links" have been continuous. What's going on? How is it that the "missing link" has been discovered repeatedly?

The problem lies in a false metaphor. When we say "missing link," we invoke a metaphorical chain, a set of links that stretch far back in time. Each link represents a single species, a single variety of life. Because each link is connected to two other links, each is intimately connected to past and future forms. Break one link, and the pieces of the chain can be separated, and relationships lost. But find a lost link, and you can rebuild the chain, reconnect separated lengths. One potent reason for the attractiveness of this metaphor is that it allows for the drama of the quest, the search for that elusive missing link.

But the metaphor is as misleading as it is attractive. The concept that each species is a link in a great chain of life forms was largely developed in the typological age of biology, when species "fixity" (the idea that species were unchanging) was the dominant paradigm. Both John Ray (1627-1705) and Carolus Linnaeus (1707-1797), the architects of biological classification (neither of whom believed in evolution), were concerned with describing the order of living species, an order they each believed was laid out by God (Ray suggested that the divinely specified function of biting insects was to plague the wicked). But while the links of a chain are discrete, unchanging, and easily defined, groups of life forms are not. [6] We generally define a species as some interbreeding group that cannot, or does not, productively breed with another group. But since species are not fixed (they change through time), it can be difficult to be sure where one species ends and another begins. For these reasons, many modern biologists prefer a continuum metaphor, in which shades of one life form grade into another. [7] Life is not arranged as links, but as shades. The metaphorical chain is far less substantial than it sounds.

Thus the chain metaphor is wrong. It doesn't accurately represent biology as we know it today, but as it was understood over four centuries ago. The myth persists because of convenience; it is easier to think of species as types, with discrete qualities, than as grades between one species and another. In school, we learn the specific characteristics of plants and animals; this alone is not a problem, except that we are not often exposed to the main ramification of evolution: that those characteristics will change through time.

Clearly, both the Post article and Broom's book describe the discovery of australopithecenes, African hominids [8] that lived well over three million years ago. Australopithecenes walked upright, like modern humans, but they had large, chimp-like teeth, and smallish, chimp-like brains. Australopithecenes made rudimentary stone tools that are more complex than any chimpanzee's termite-mound probe stick, but far less complex than the symmetrical tools made by early members of our genus, Homo. In terms of anatomy and behavior, some australopithecenes really do appear to be "half human." Additionally, it's widely believed that early Homo descended from some variety of late australopithecene. Broom was right after all, but so was the Post; a "missing link" has indeed been found. It is Australopithecus. But there were many varieties of Australopithecus, as well as Homo, and there is no obvious place to draw a discrete line separating a shade of late Australopithecus from an early grade of Homo. Therefore, it's more accurate to say that we have found some "grade" or "shade," rather than "the missing link." [9]

We can curb the false metaphor by changing our wording. In classes, in textbooks, in discussions with our students, and in press releases (the critical connection between academia and the general public), we have to start saying that we're looking for a missing link, rather than the missing link. Better yet, we should replace the "missing link" stock phrase with something more accurate.

6 The species concept is introduced in Strickberger (1985:747-756), but also see Mallet (1995) for the need to review how we define species.

7 Lions and tigers once coexisted naturally in India, and although they are outwardly very different, they can mate to create tigons or ligers. Since such hybrids were never found in nature, however, it is known that lion and tiger did not interbreed naturally. Thus, genetically, lion and tiger can be classified as one species, but behaviorally, they differed enough to be considered separate species by biologists, and in nature this difference was maintained by the animals themselves (Wilson 1977:7).

8 Hominids are large primates that walk upright. Those of the genus Australopithecus (which predate the human lineage Homo) are referred to as australopithecenes. They appear over 4 million years ago. Many hominid varieties have existed, but Homo sapiens sapiens is the only living hominid.

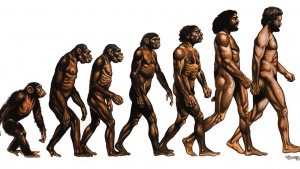

9 The link metaphor also suggests that any given species is represented by only one chain, as when we see a diagram of hominids, first knuckle-walking, then hunched over in a half-stand, then upright as modern man. This depiction does not show several other bipedal hominid varieties to which we are related, such as the robust australopithecenes (appearing over 4 million years ago, disappearing about 1 million years ago) or the Neanderthals (who appear around 300,000 years ago and are extinct by c.30,000 years ago). The depiction suggests that there was one, unbroken chain, from quadruped to biped, but actually there have been bipeds that have gone extinct (as well as quadrupeds that exist today).